Why we lose historic buildings — and ways to protect them

Chattanooga has preserved fewer historic parts of town than peer cities despite having the same tools for protection.

By William Newlin

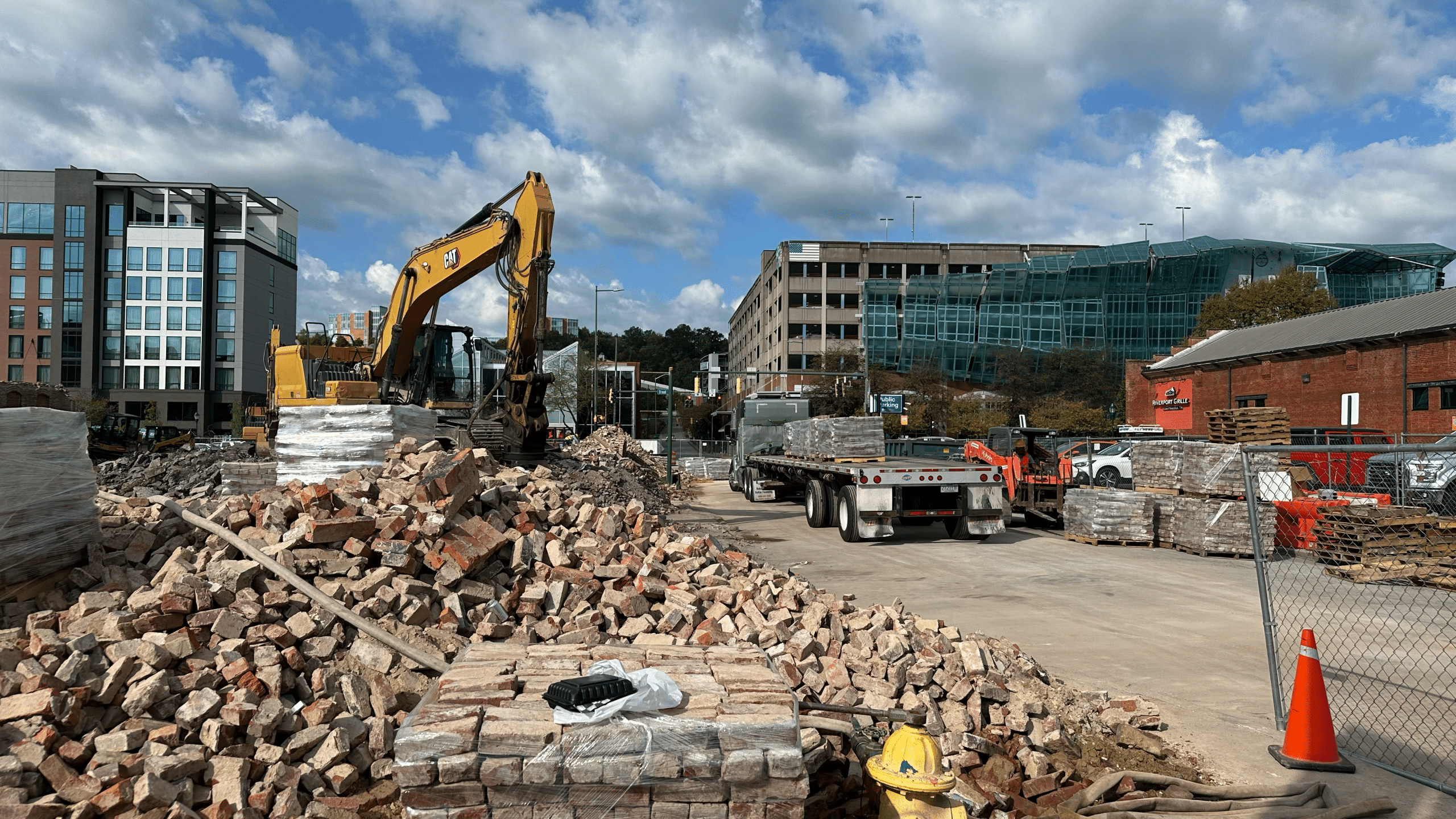

The former Sports Barn building on Market Street was a direct connection to Chattanooga’s transportation past. Built in 1886 to shelter street cars and the horses that drew them, it later housed some of the electric trolleys crisscrossing the city. Today, the site is a pile of bricks, razed to make way for a new hotel.

On McCallie Avenue, the 1928 Medical Arts Building is also slated for demolition due to the high cost of renovations, owner First Presbyterian Church has said. Famed local architect R. H. Hunt designed the tower, adding to his portfolio of iconic structures — the Tivoli, the James and Maclellan buildings, City Hall, the federal courthouse, and the Hamilton County Courthouse, to name a handful.

The apparent vulnerability of the city’s historic properties has left some Chattanoogans wondering what they can do to protect other beloved facades.

What is protected?

📍 In Chattanooga, four neighborhoods and eight buildings have various levels of protection:

- Homes in four historic districts (Fort Wood, Ferger Place, Battery Place, and St. Elmo)

- The Shavin House on Missionary Ridge, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright

- The facades of seven buildings:

- Terminal Station (Chattanooga Choo-Choo), 1400 Market St.

- Customs House, 31 E. 11th St.

- Trigg-Smart Building (next to Tivoli), 701 Broad St.

- Hotel Clemons, 730 Chestnut St.

- The Dome Building, 736 Georgia Ave.

- The Warner House, 800 Vine St.

- The Dent House, 6178 Adamson Circle

↖️ By comparison, Nashville has:

- Nine historic preservation zones with strict rules on construction and alterations, similar to Chattanooga’s local historic districts

- 27 neighborhood conservations districts with more flexible rules

- 72 protected landmarks

↗️ And in Knoxville:

- Six historic districts

- Five neighborhood conservation districts

The state of Tennessee certifies local governments with active preservation programs, and there are various ways cities and counties set them up. Both Nashville and Knoxville use overlays in their zoning code to protect certain parts of town.

Chattanooga’s process, although not included with other zoning rules, functions the same way. We’ll get into how it works below.

⚠️ What about the National Register of Historic Places?

Dozens of local sites appear on the National Register of Historic Places, but the designation doesn’t put rules on alteration or demolition. That means property owners can do whatever they want with the majority of Chattanooga’s historically significant buildings.

A few routes for historic preservation in Chattanooga

1️⃣ The Historic Zoning Commission: Property owners, neighborhood associations, civic groups, and City Council can submit applications for local historic districts and landmarks to the Historic Zoning Commission.

The commission weighs the site’s connection to important people, events, architectural styles, or cultural identity to decide if it should receive historic status. If approved, any plan to modify or demolish a building is subject to review by either city staff or the commission.

But this process is rarely used — it’s been more than 30 years since the commission has granted protected status to a district or landmark.

Cassie Cline, the City of Chattanooga’s historic preservation planner, said an application to give landmark status to the Chattanooga School for the Arts & Sciences is currently under review. In the past year, multiple neighborhoods have shown interest in becoming historic districts, she said, though none have applied.

“ I think retaining our built environment is a great thing, so if people have questions about it, they’re interested in it, I’m happy to have that discussion,” Cline said. “That’s what I’m here for.”

2️⃣ Facade Easement: A facade easement is the “strongest tool” to protect a building, said Todd Morgan, head of local nonprofit Preserve Chattanooga. Attached to a property deed, easements are legal tools that permanently restrict what can happen to a building’s exterior.

Groups like Preserve Chattanooga can “hold” an easement, assuming responsibility for enforcing those restrictions. Easements are only available to property owners. Concerned citizens, for instance, cannot set up an easement on privately held property.

Just seven Chattanooga properties have facade easements monitored by Preserve Chattanooga, including the Choo Choo and the Dome building on Georgia Avenue. The latter’s iconic cupola, cornice, and brickwork aren’t going anywhere.

Adding an easement to a private home can cost a few thousand dollars to cover legal counsel and monitoring over time, Morgan said. If a property is on the national register, easements can also provide federal tax deductions.

3️⃣ Public pressure?: Over 2,000 people have signed a petition to save the Medical Arts Buildings from a planned demolition this fall. Property owner First Presbyterian Church has said upkeep and repair are more expensive than replacing the tower with an up-to-date church campus extension.

“Yes, the response surprised us,” local petition creators Robert Glover and Annya Shalun wrote in an email to Chattamatters. “It’s wonderful. Chattanoogans do deeply care about what happens here.”

Lobbying for a local historic designation to protect the Medical Arts Buildings isn’t off the table. But as the petitioners know, and both Cline and Morgan noted as well, approval from the Historic Zoning Commission and City Council is unlikely without the property owner’s support.

Glover and Shalun’s last recourse is to push for an ownership change. They’re urging church leadership to consider any offers from buyers willing to preserve the almost 100-year-old high-rise, which has a personal connection to Glover. His grandmother worked there as a switchboard operator in the 1960s and 1970s, he said.

The buy-and-save model isn’t unprecedented in Chattanooga. Stewards with access to capital committed to adapt Warehouse Row, the Read House, and the Chattanooga Bank Building for modern use.

“It’s more money than can be crowdsourced,” Glover and Shalun wrote. “It is the money of developers. If anybody knows how to get the right person’s ear for something like this, they need to come forward.”

New rules for preservation?

A couple efforts are underway that may make historic building preservation easier in Chattanooga and Hamilton County.

- Preserve Chattanooga received grant funds to create a new preservation plan covering Hamilton County. Morgan said the plan will include policy proposals, like a local tax incentive, to encourage more owners to protect their buildings.

- Cline’s office is working to combine the four historic districts’ design guidelines into a single document and streamline the review process for some minor property changes. She said staff and residents have also discussed possible historic zoning updates, such as creating more flexible conservation districts like in Nashville and Knoxville.

“ Cities grow and change, and things age,” Morgan said. “That’s why we have to be diligent and really try to plan ahead for what we can do to help these places.”

Contact William at william@chattamatters.com