Tennessee’s lost county

Now mostly forgotten, James County lay next door to Hamilton for almost 50 years. Here’s why it fell off the map.

By William Newlin

Mountain Oaks Manor in Ooltewah hosts all kinds of events — weddings, tea parties, last month’s Harry Potter night. The rooms inside express a turn-of-the-century, celebrate-the-special-day kind of charm, decked out in rugs, wreathes, chandeliers, and floral tablecloths.

On the register of historic places since 1976, the two-story brick mansion served as the third and final James County courthouse more than a century ago. As she gives a tour, owner Sonya Guffey describes the history underlying her period decor.

The pink-walled tea room was once a jail, she said. In the bridal suite upstairs, the judge would prepare for court, which convened in a space that now holds micro-weddings and receptions.

James is the only county to have ever come and gone in the history of Tennessee, and this converted relic on Mulberry Street is one of the few reminders of its brief existence.

Born out of resentment toward an up-coming Chattanooga, James formed between Hamilton and Bradley counties in 1871. After five turbulent decades, financial failure ultimately took it off the map.

Here’s the story of Tennessee’s lost county.

‘Rival villages’

In 1870, Chattanooga overtook Harrison as the seat of Hamilton County. According to an 1890 retelling in the Chattanooga Daily Times, some residents of Harrison and the eastern part of the county “were much incensed” by the move.

It was another gut punch in the years-long bout between the “rival villages,” which Chattanooga won by securing a spot along key rail lines.

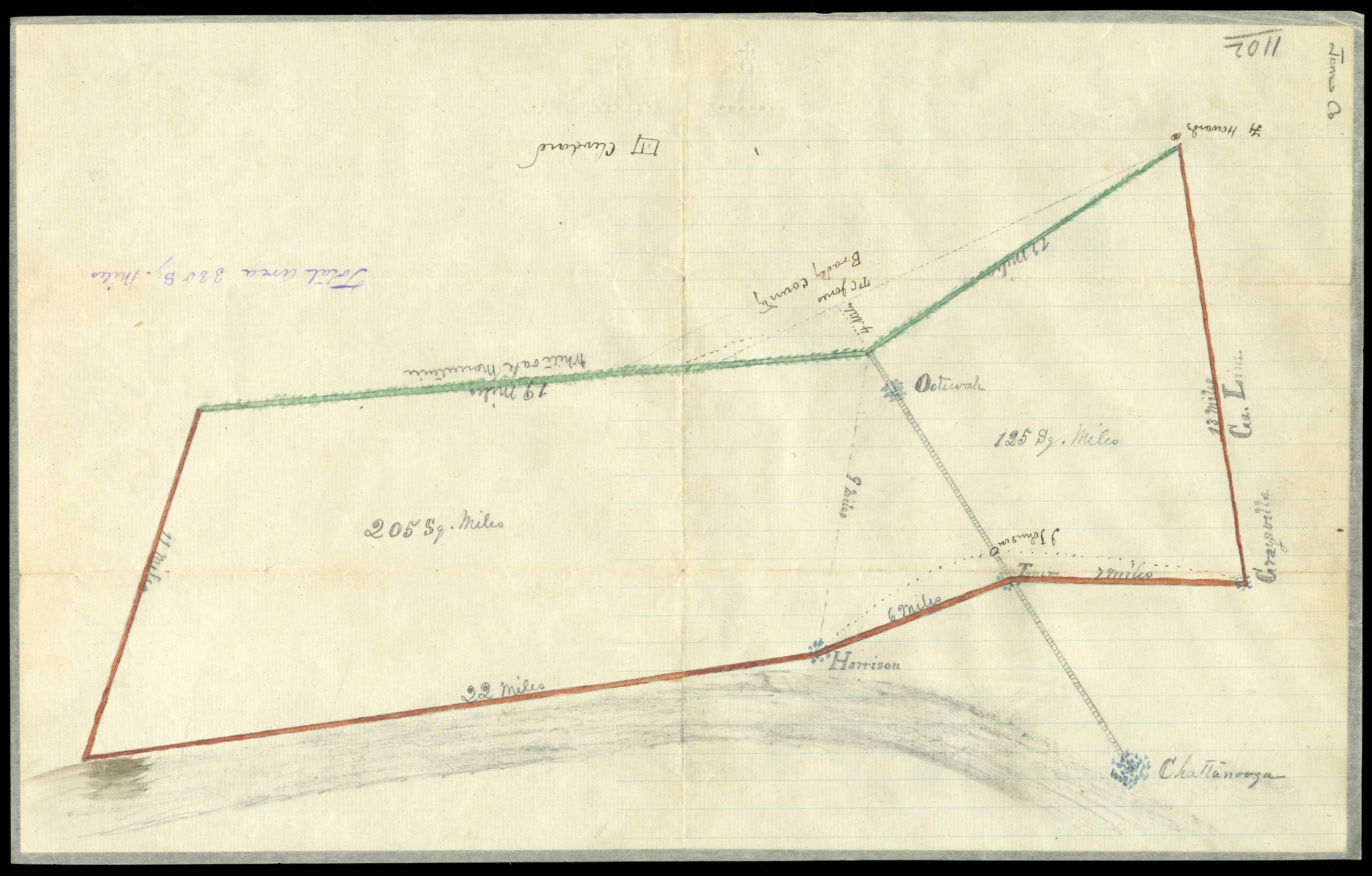

State legislator Elbert A. James responded to the seat snub by proposing a new county next door. The legislature granted his request, and James County — named for Elbert’s father — took shape. (See the image at the top of this article for a contemporary map of James County.)

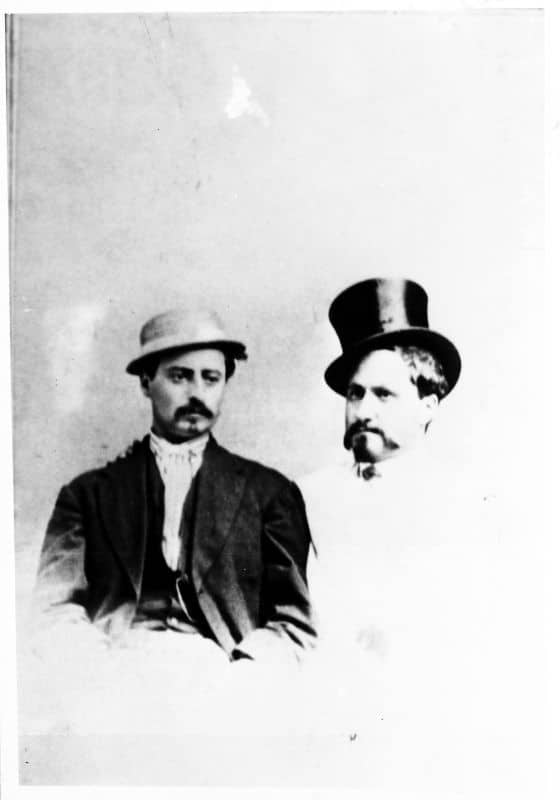

Elbert A. James (right) with unidentified man, 1880. (Photo courtesy Chattanooga Public Library)

Elbert James doesn’t appear much in the historical record. An 1885 obituary in the Chattanooga Commercial claimed he sympathized with the Union during the Civil War and sought to quickly restore “fraternal relations” post-conflict. A 1983 book published by a James County historical society wrote he served as a Union colonel. Although sometimes referred to as “Col. Eb. James” in contemporary news reports, no remembrances mentioned high-ranking military service. As a state legislator, he sponsored an 1870 resolution rejecting the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which extended the right to vote to formerly enslaved men.

In a twist of irony, Harrison lost out in James County, too. Voters chose Ooltewah as the new county’s seat, and the first public buildings cropped up in the early 1870s.

An existential crisis

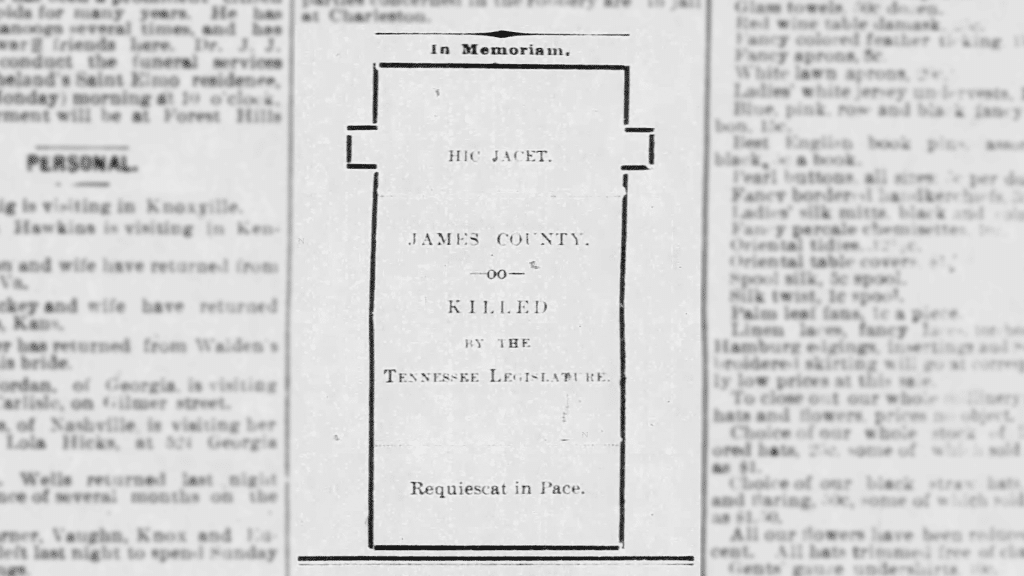

James County’s courthouse, and most of its records, burned in a suspected arson in January 1890. The Times reported a couple weeks later that officials decided not to rebuild, and some residents had begun a petition to give up James’ county status.

“This is the time to disband if it is to be done at all,” Dr. B. W. Padgett of Ooltewah told the Chattanooga Republican.

Then-governor Robert Taylor agreed, signing a law to dissolve the fledgling county in a special legislative session. Legal chaos ensued for the next seven months.

Some James residents — irate they had no say in the state government’s decision — filed suit against the “radical legislation,” per the Times. That gave them some time to make the case for James’ existence.

And although a local judge upheld the law axing James, he prevented the transfer of James County’s land, revenue, and remaining records back to Hamilton and Bradley.

As local elections approached in August, the Daily Times expressed everyone’s confusion: “Does James County now exist?” the paper wondered.

Hamilton County said no and divvied up its returned portion of James into new voting districts. James County said yes and formed its list of candidates at a July meeting that ended with “three cheers for old James,” per the Times.

Voters, meanwhile, got caught in this jurisdictional limbo. They faced a dual election featuring ballots from both counties (except in Ooltweah, where officials refused to field its neighbor’s tickets).

Available records are unclear on whether James County voters impacted elections for sheriff, trustee, and register in Hamilton, though the Times called the James vote “very light.”

Local governance remained foggy in the region until the state Supreme Court intervened in October. The law abolishing James County was unconstitutional, the court said, and those elected to the Hamilton court from districts in the resuscitated James County territory never took office.

In April 1891, James County decided to reconstruct its courthouse, “a handsome brick and stone affair, built in the renaissance style,” as the Times described it a few years later.

But as a 1983 book published by a James County historical society recalled: “The opponents of the county never gave up.”

The waning years

Rumblings of annexation to Hamilton County had returned by the early 1900s. Key concerns were poor roads and a lacking school system, both underfunded due to a limited, agricultural tax base.

“A farmer’s wife” expressed her frustration at the state of the county to the Times in February 1912: “Why, then, do we not have good roads when there is available material on hand to build them? Why are there no telephones? Why are there no reading clubs or debating societies among the young people?”

A year later — and just two days after local and state officials discussed a citizen-led push to dissolve the county — news of another courthouse fire emblazoned Chattanooga papers. James County Clerk Sam Lovell’s arrest for arson caused a major media stir months later, though it never led to an indictment.

The incident had the opposite effect of the 1890 blaze, igniting support for local independence and improved infrastructure. Although the third and final courthouse arose within a year, James residents’ renewed patriotism didn’t survive long.

Bankruptcy rang the death knell for James County in 1919. Once more the legislature passed a bill abolishing the hard-pressed county, but lawmakers had learned: It would be up to voters to decide their fate.

Like nearly every decision about James, this final annexation act wasn’t without legal controversy. The legislature actually passed two bills, one giving a small sliver of James back to Bradley County and the rest to Hamilton. Those destined for Bradley wouldn’t have a say in the vote on dissolving James. Affected residents filed suit and won.

Every James County voter had a choice to make come December. Despite concerns from farmers about a Hamilton County law that required a costly “hog-tight fence” around properties, James County overwhelmingly opted for annexation.

Here’s how the historical society put it:

“James County is gone. It now exists only as a part of the history of this community and in the hearts and memories of its citizens.”

Contact William at william@chattamatters.com